In Bloom: Iris ensata

The much-revered Iris ensata is a Japanese native, and an important early-summer element of Seattle Japanese Garden.

The Japanese iris now known as Iris ensata (hanashobu in Japan) is an iconic element in Japanese gardens, and references to it in Japanese literature and art date back to at least the 12th century. It’s a popular motif in textile art, and is frequently used in flower arranging (ikebana).

Hanashobu is an important, early-summer element of our Seattle Japanese Garden – and Japanese-style gardens throughout the world, wherever it thrives. Once referred to as Iris kaempferi, its original botanical name (Iris ensata) was revived in 1985.

In Japan, iris culture is an art, like many practices that have been developed over centuries. Beginning at least 500 years ago, the Japanese have developed more than 2000 cultivars (cultivated varieties) from the original wild plants. We recognize these cultivars by their large, beautifully colored and patterned flowers, notable for their wide falls (the flower parts that hang down) and graceful, horizontally spreading form. They’re herbaceous (non-woody) plants that die to the ground in winter. They have bold straplike foliage, and are often more than 3 feet tall. Full sun, and very moist, acid, humus-rich soil is required, along with ample fertilizer. The large flowers appear in June – usually in colors of blue, purple, purplish-red, and/or white, and often with contrasting patterns of dots, stripes, veins and rims. Many cultivars have ruffled flowers, and some are doubles, with multiple flower parts.

The wild parent plant (Iris ensata var. spontanea) is native to Japan, Northern China, Manchuria, Korea and Siberia. A perennial plant growing from rhizomes, it grows in marshes and wet, grassy places. Flowers, usually reddish-purple with a streak of yellow, consist of fairly wide falls and small narrow standards (the upright petals). In ancient times, farmers quite likely planted wild irises in or near their rice fields -- because they needed to rely on seasonal changes to direct their labors. Iris were important signal plants because their blooming coincided with the start of the rainy season, the time for transplanting rice plants from seed beds to the fields.

Over the centuries, three strains of Japanese iris were cultivated, named for the areas where their development took place. The Edo strain, which includes the oldest and less developed forms, was from the area around Tokyo, where plants of many colors were collected and hybridized. These cultivars were raised in the fields and their flowers had to withstand outdoor conditions. They had a wide range of colors and patterns, but were fairly simple in form.

The Higo strain came from the area around Kyushu, and plants were bred for white and bold colors, without the patterning found in the Edo strain. This area had heavy rains, so they were bred to be grown in pots and enjoyed indoors. Elaborate traditions were developed that determined how they were to be displayed.

The Ise strain came from the Kyoto area, where they were associated with religious shrines. This strain included very delicate cultivars in pale colors, often in shades of pink. These flowers lacked the substance to withstand outdoor conditions, so like the Higo strain, pot-grown plants were displayed indoors. The form of their flowers was carefully controlled to maintain the delicacy that was prescribed.

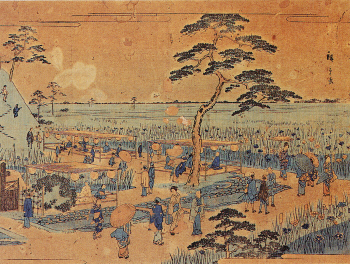

Irises that had been developed to grow outdoors were planted in huge display gardens, and people came to the gardens in large numbers when the plants were in bloom. This tradition, similar to that of visiting the cherry trees during their blooming season, continues in Japan even today. A woodblock print by Hiroshige, the famous ukiyo-e artist, depicts the Kotaka-en hanashobu garden near Tokyo, with its three viewing pavilions, rows of irises and many visitors:

Woodblock print by Hiroshige, depicting the Kotaka-en hanashobu display near Tokyo.

In Japan, and in Japanese-style gardens elsewhere, Iris ensata is often used in mass plantings on the edge of ponds or beside small streams, sometimes next to yatsuhashi (zigzag) bridges. The Seattle Japanese Garden has many iris beds along the edges of our central pond.

Cultivars were introduced into Great Britain and the United States in the 19th century, and both countries have continued to develop new cultivars, numbering in the thousands. Hanashobu enthusiasts everywhere have a wealth of riches from which to choose. Individual flowers are not long-lasting, so they invite us to appreciate their fleeting beauty in the present moment.

Corinne Kennedy is a trained guide for Seattle Japanese Garden and a contributor to the garden's blog.