The History of Japanese Children’s day

By Yukari Yamano

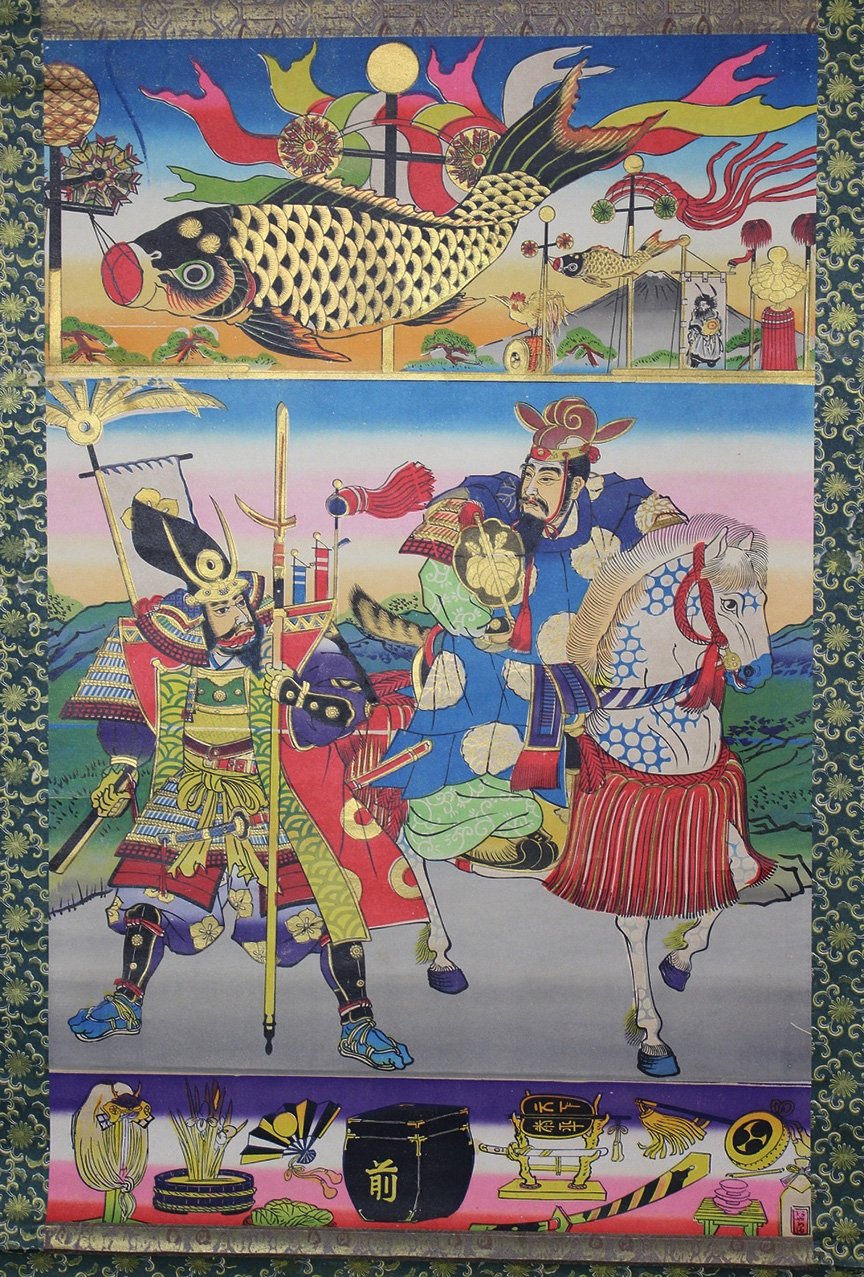

Dragon Boat Festival hanging scroll decoration From the end of the Meiji era to the Taisho era Japan / Japanese paper / wood from Japan Toy Museum

May 5th is Children’s Day in Japan. In 1948, it was designated as a national holiday by the Japanese government, and the name was changed from Boy’s Day to make it a day to respect all children's personalities, celebrate their happiness, and thank their mothers. Yes, thanking mothers is part of Japanese national-holiday law!

To mark the holiday—and express hope that their children will be healthy and strong—families traditionally fly Koinobori, or carp-shaped windsocks, outside their homes and decorate samurai dolls and/or warrior helmets, and place these in an alcove inside their homes. They also enjoy eating Kashiwa Mochi (sticky rice cake filled with sweet red bean and wrapped in oak leaves) and Chimaki (sticky rice wrapped in a bamboo leaf). The leaf wrappings have cultural significance: Oak leaves are considered auspicious, while Chimaki was originally wrapped in the leaf of Chigaya, or cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica), which was believed to ward off evil.

Shobu, Acorus calamus from Wikipedia

The historical roots of Children’s Day run very deep, all the way back to the Nara period (710 to 794). Originally, the celebration came from China and was called Tango no sekku (端午の節句). From the Nara period to the Heian period (794–1185), it was one of five seasonal ceremonies conducted in the Japanese imperial court. Tan (端) means "beginning," Go (午) is the symbol for a horse from the Chinese zodiac, representing the fifth lunar month, and sekku means “festival.” Tango no sekku was held on the fifth day of the fifth moon and was an important apotropaic—evil averting—event.

The significance of sweet flag (Shobu)

On the Lunar calendar, the fifth day of the fifth moon actually happens in the month of June on the Gregorian calendar. (Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar in the late 19th century.) June in Japan is a rainy season, historically fraught with natural disasters and epidemics. It was a time of year when people would easily get tired or sick. Because of this, Tango no sekku became strongly associated with Shobu (菖蒲), sweet flag (Acorus), a strongly scented perennial herb that was used medicinally and believed to get rid of bad luck. On the festival day, at the imperial court, sweet flag was put on roof eaves, and Kusudame, an ornamental scented ball made with sweet flag, was hung on pillars to ward off evil spirits.

Court nobles consumed sweet flag in various forms. People drank sake with chopped sweet flag in it, took baths with sweet flag leaves floating in them, and slept on a Shobu makura, a sweet flag pillow. Sweet flag was also wrapped in a thin paper and put by people’s pillows as an amulet against evil. Because of the use of sweet flag, Tango no sekku was also known as Shobu no sekku.

Contemporary sample image of sweet flag put on the eave of the gate from Fukujuya

Contemporary sample image of sweet flag bath from Hotel Kuu

Because in Japanese Kanji (logographic script), Shobu (菖蒲) could be written as Shobu (尚武), meaning “martial spirit,” and because the shape of the sweet flag leaf resembles a sword, samurai of the Kamakura period (1185–1333) adopted the Shobu no sekku ceremony and changed it into a celebration for their young warriors.

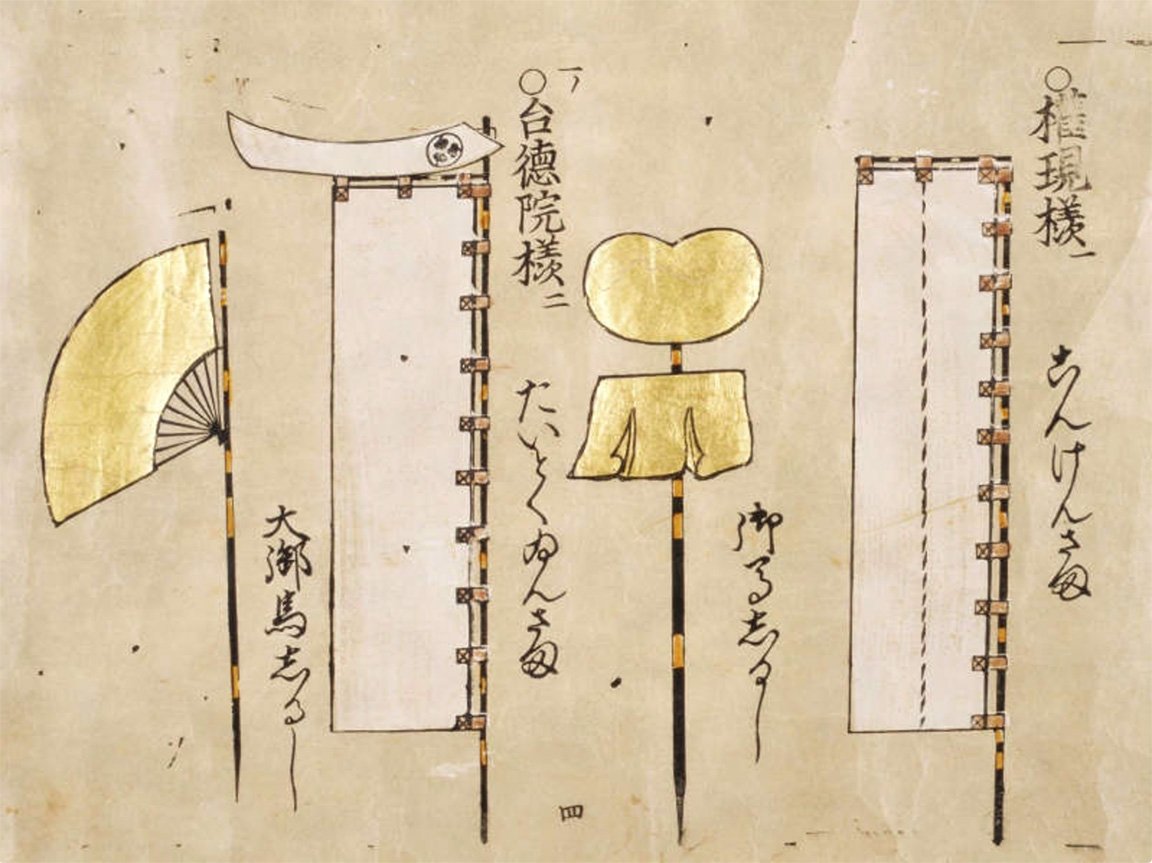

During the Edo period (1603–1868), Shobu no sekku became one of the Tokugawa Shogunate’s important annual ceremonies, and the date was moved and fixed to May 5th. Feudal lords in their very formal attire visited Edo Castle (in modern-day Tokyo) to celebrate Tokugawa Shogun. When the heir was born, the Shogunate conducted this ceremony, grandly decorating the castle with banner flags, warrior’s helmets, and swords.

This custom spread through the eastside of Japan, where Edo (Tokyo) was located, and samurai families started to put Nobori (a banner flag with their family crest), Umazirushi (a fan ornament), and/or Fukinagashi (a windsock)—which were originally arranged at ancient battle fields—at their gates to honor their military achievements and pray for their son’s promotion.

From celebrating young warriors to young sons

In the mid-Edo period, while the city of Edo was stable and peaceful, merchants who gained power started to celebrate Tango no sekku for their sons. Because they were not allowed to decorate their homes with traditional warrior equipment, they substituted with ornamental paper helmets and carp-shaped streamers.

They adopted a carp for the streamer because, in Chinese legend, it was said that if a carp passed through the gate of the top of Hwang Ho (Yellow River) during the mating season, it would become a great dragon and ascend to heaven. Merchants put Koinobori outside of their house to hope for their son’s health, happiness, and advancement in life.

Since then, carp-shaped streamers flying in the sky during this season have been greatly appreciated by many Japanese. At the Seattle Japanese Garden, colorful Koinobori are put over the pond to celebrate Koi Day, May 14th. Come and see them yourself, and let’s celebrate our children’s happiness together.

Koinobori at the Seattle Japanese Garden 2017

Yukari Yamano is a special projects coordinator at the Seattle Japanese Garden, a native Japanese and a Japanese history buff.